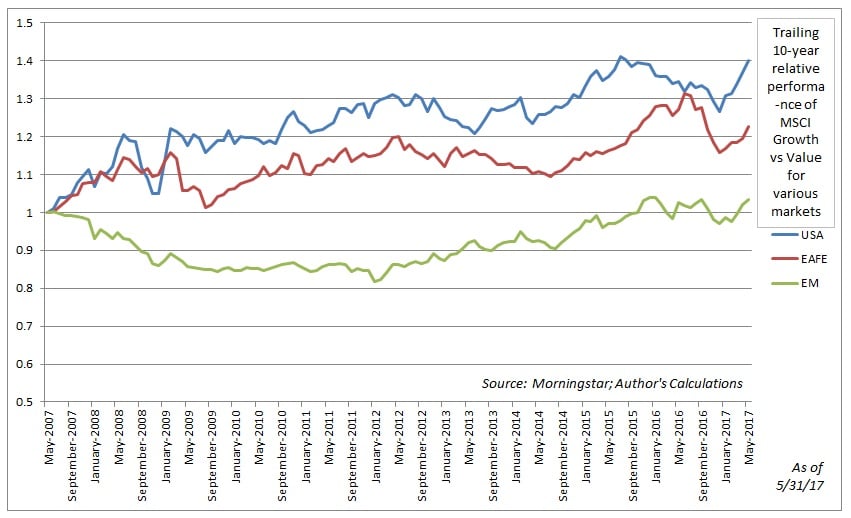

Going back to December of 1974, value stocks have outperformed growth stocks by an average of more than 200 basis points per year.* Yet over the last ten years, growth stocks have outpaced value stocks in every major segment of the global market:

While it has not been the greatest period of relative outperformance, – that honor belongs to the tech bubble of the late 1990s, – the last ten years have been the longest period of strong relative performance for growth compared to value going back to 1974:

This is uncharted territory for value investors, who are used to trouncing their growth-oriented counterparts. Given this seemingly apparently paradigm shift, so to speak, it would be hard to blame them for questioning the continued merit of value investing, even though it has historically delivered out-sized returns in all markets, including foreign developed, and emerging.

It can and should be argued that the last ten years have been anomalous from a historical perspective. After all, in the last ten years, the world markets have suffered through a once-in-a-lifetime financial crisis which sank global bank shares, and also the worst oil price collapse in a generation. Those two events have punished value strategies, which rely heavily on the price-to-book metric as a measure of value. Since low price-to-book ratios are a common feature of many financial and energy stocks, value portfolios relying on that metric usually end up with heavier concentrations in financial and energy stocks.

For example, in the MSCI EAFE Value index, the financial and energy sectors make up roughly 45% of the portfolio (36% and 9%, respectively). In the MSCI Emerging Markets Value index, those same two sectors total 46%, though the distribution is a bit more even at 35% financials, and 11% energy. In the US, those two sectors account for much less (roughly 30% combined of the MSCI Value index), so that likely explains why the value portfolio has held up much better domestically.

Whatever the reason for value’s miserable decade, it is no reason to abandon the strategy altogether. After all, true value investing is about being a contrarian. Similar to a GM of a sports team who sees upside potential in a good player coming off an injury, a contrarian investor sees potential in the beaten down shares of a company. In investing, your money is made on where you buy into a venture, and logic dictates that paying $.50 for something you feel is worth a $1 is going to outpace a growth strategy that more or less relies on selling a $1.10 for $1.20 to a (theoretically) greater fool.

The important question to be asked is not whether value investing is dead, but rather what will propel it back to the forefront? For energy shares, the answer is obvious: higher fossil fuel prices. For bank shares, it could be something regulatory, such as the relief of some post-crisis rules that have inhibited bank profitability. It could also be something behavioral in nature, by which I mean that as memories of the financial crisis fade, value-oriented investors may once again find bank stocks attractive.

On a broader note, the recipe may simply be something like a return to economic normalcy. Since the financial crisis, the global economy has been remarkably uneven with growth anemic at best, and any company showing signs of sustained growth has been rewarded handsomely. It is telling that the MSCI World Growth index is led by “category killers” such as Alphabet, Apple, and Amazon, which dominate their sectors. In fact, Growth has benefited from concentrations not just in a few winning sectors, but in a handful of winning firms; the top ten holdings of the MSCI Growth Index constitute almost 28% of the index, whereas in the comparable Value index, the top ten holdings account for only 16% of the portfolio. If economic growth were to return on a more balanced and sustained basis, it is likely that the benefits would filter through to wider parts of the market where value is currently more likely to reside.

It is important to note that not all ‘value’ strategies have suffered the last few years. For example, the S&P 500 Buyback Index, which is composed of more than one hundred stocks that are, on average, considerably cheaper than the broader market, has outpaced both Growth and Value:

In sum, it is easy to look back over the decades of historical performance and think that the rich rewards earned by value investors came easily. What the historical records do not show you is that those successful value investors stomached very long periods of underperformance if not self-doubt, while alternative strategies raced ahead. Arguably, good investor behavior is more important in value investing than in any other aspect of investing as it requires discipline and patience on a level that most investors simply cannot meet. The next ten years may be as difficult for value investing as the last ten have been, but the strategy should still yield handsome rewards to those who can afford to wait.

*As measured by the MSCI World Value & Growth indices

Disclosure: The results are hypothetical results and are NOT an indicator of future results and do NOT represent returns that any investor actually attained. Indexes are unmanaged, do not reflect management or trading fees, and one cannot invest directly in an index.

This writing is for informational purposes only and does not constitute an offer to sell, a solicitation to buy, or a recommendation regarding any securities transaction, or as an offer to provide advisory or other services by Fortune Financial Advisors, LLC in any jurisdiction in which such offer, solicitation, purchase or sale would be unlawful under the securities laws of such jurisdiction. The information contained in this writing should not be construed as financial or investment advice on any subject matter. Fortune Financial Advisors, LLC expressly disclaims all liability in respect to actions taken based on any or all of the information on this writing.