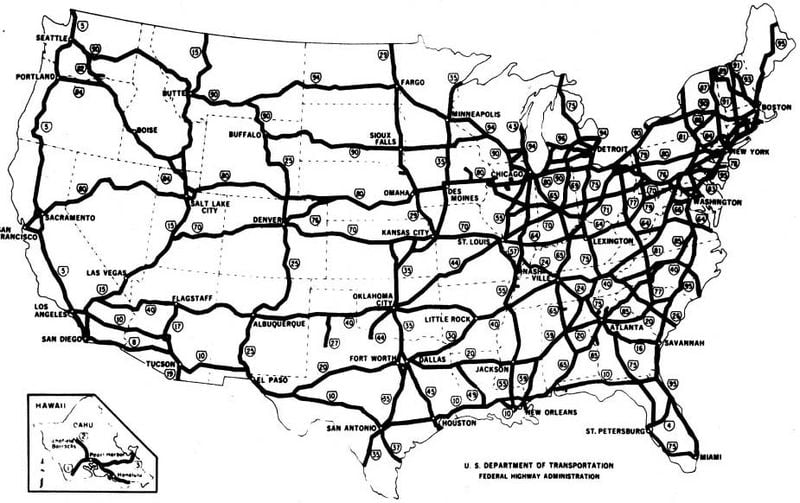

Signed into law in 1956 by then President Dwight Eisenhower, the Federal Highway Act created the Interstate Highway System, which would become the largest and costliest public works project in history. Measuring almost 48,000 miles in total distance, the Interstate Highway System was completed only in 1992, more than three decades after work began, and for a total cost in today’s dollars of more than $500 billion.

(source: Wikipedia Commons)

Inspired in large part by the German Autobahn, President Eisenhower envisioned a coast-to-coast network of high-quality paved highways that would serve a multitude of purposes, from facilitating faster travel and greater logistical flexibility (the railroad networks had been stretched to their limits during the World Wars), to aiding in military resupply in times of war or evacuations in the event of a national catastrophe. The greatest and most immediate impact, however, was economic; researchers at the University of California, San Diego estimate that for every $1 put into building the interstate highway system, $1.80 was returned in greater economic activity. With travel distances between the coasts cut down from weeks to days if not hours, the United States became a much more mobile society with entire regions now open to consumer-driven travel and further industrialization.

First, however, the interstate would have to be built, and that required a lot of manpower, machines, and material. In his wonderful history of the Interstate, The Big Roads, Earl Swift writes:

“Each billion dollars spent on construction provided the equivalent of forty-eight thousand full-time jobs for a year and consumed an almost inconceivably vast pile of resources: sixteen million barrels of cement, more than half a million tons of steel, eighteen million pounds of explosives, 123 million gallons of petroleum products, and enough earth to bury New Jersey knee-deep. It also devoured seventy-six million tons of aggregate– so much aggregate, some in the business have surmised, that the United States could not mine enough rock to rebuild the interstates today.”

Among the beneficiaries of this huge outlay were the quarry owners and aggregate miners, who provided the gravel and rock on which the interstates were laid, the heavy machinery manufacturers who provided the graders, tractors, and steamrollers that turned those rocks into roads, and the oil and gas producers and refiners who made the gasoline and diesel that fueled the project. Some of the firms involved in the creation of the interstates took the opportunity to advertise their participation in the great national project, such as this 1961 ad from Caterpillar [via Transit Maps]:

As families began to set out exploring the country on the new interstate system, restauranteurs such as Ray Kroc and Howard Johnson recognized the need to provide traveling families with predictable, familiar service. The idea of the chain restaurant was born as interstate exit ramps guided hungry motorists to McDonald’s and Howard Johnson’s. Families would also need places to say on longer journeys, so hotels followed restaurants in the chain model as franchises like Holiday Inn became a staple of interstate exits; early ads for the hotel underlined the value of the familiar by stating, “The best surprise is no surprise.”

The logistical flexibility provided by the interstate system also gave rise to a whole new model of retailing: big box stores began to set up in small towns offering rich variety and low prices to consumers previously left unserved by larger retailers. Walmart’s 1975 annual report detailed just such a model:

Whereas not quite a century before the railroads had aided in the rise of Sears, Roebuck, and Co. as the first retailer with national reach, the interstate in the 1960s and 1970s would provide the backbone of Walmart’s logistical operations, with large distribution centers situated at critical points throughout the interstate network to facilitate inventory replenishment, as Professor Jesse LeCavalier has noted on his blog (map of Walmart distribution centers via Jesse LeCavalier):

Southern states like Tennesse (home to Fedex) and Arkansas (home to Walmart, JB Hunt, and others) saw their economic fortunes change in large part to the interstates as the new highways allowed them to become manufacturing centers of choice given they typically had lower labor costs than their Northern and Midwestern counterparts, and many were situated at ideal points in the country to become logistics hubs. Prior to the creation of the Instate Highway System, for example, Arkansas’s per capita personal income hovered around 60-65% of the national average; after the interstates were created, that number grew to 75% in the mid-1970s, and is around 80% today:

In sum, the Interstate Highway System changed the face of American society and business forever. It reduced regional fragmentation as distances became shorter. It strained old industries such as railroads with new, disruptive competition, and gave rise to entirely new business models as small town America became the hunting ground for large, faceless corporations.

This post is meant as a kind of overview of some of the main talking points as it relates to the Interstate Highway System; we plan on covering these topics in greater detail in an upcoming miniseries on the Preferred Shares podcast, which you can find on your favorite podcast app.

This post is purely for informational purposes; any mention of specific companies is not to be construed as a recommendation of any kind. The author, as well as employees and clients of Fortune Financial Advisors, LLC may hold positions in any stocks mentioned, though that is subject to change at any time.