Perhaps because people choose to believe popular narratives over overwhelming evidence, many myths persist in the financial realm. In a way, this should not be surprising as many things in finance seem intuitive, but in reality, are much more complicated than we might think. In this article, I will attempt to put to rest two myths that seem to be prevalent today.

I. Fewer Public Companies Mean Higher Multiples

It has recently been argued by a couple prominent financial commentators (see here and here) that the phenomenon of far fewer public companies existing today versus twenty years ago should necessarily mean higher than (historically) average equity valuations. The logic seems to make sense: investors have to invest for retirement, so the demand for stocks is at least constant if not rising, while the supply of stocks is shrinking. In theory, this should be a classic case of supply and demand working themselves out in favor of higher prices. There are several problems with this thinking, however.

First of all, equity “demand” on the part of households is almost always negative. That is, households and the financial institutions that serve them are almost always engaged in net selling, as Matt Klein has pointed out. This makes sense as households, in aggregate, are engaged in net spending, while corporations themselves are typically net savers, which results in companies buying back their own shares from individuals, institutions, and the like, who use the proceeds for whatever.

Secondly, the idea that the stock market is “shrinking” is simply misguided. Even though there have been far fewer IPOs of late than in the past, overall equity issuance has been relatively constant:

(chart via Matt Klein / FT Alphaville)

This matters because investors are not buying companies or ‘the market’ so much as they are buying the earnings of companies or ‘the market.’ Whether the market consists of 100 stocks or 10,000 stocks is largely immaterial to valuations. Think of it like this: most companies disappear from the public ranks through mergers and acquisitions (“M&A”). If a market of 200 stocks condensed into 100 stocks due to M&A, the aggregate earnings power is more or less unchanged, so it follows that the valuation should not change all that much, either. Conversely, if a market of 100 stocks expanded to 200 stocks solely through spin-offs, the effect is the same: aggregate earnings power remains the same, so valuations will stay constant, too. In sum, there are many plausible reasons for higher than average equity valuations, but fewer public companies is not one of them.

II. Investors Need To Own Every Stock

When asked recently what was his favorite stock, Vanguard’s CEO, Tim Buckley, replied, “All of them!”

While this comment is certainly no surprise coming from the CEO of a fund manager famous for its passive approach to investing, the idea behind it is misguided. There actually seems to be no tangible benefit to owning every stock in the market.

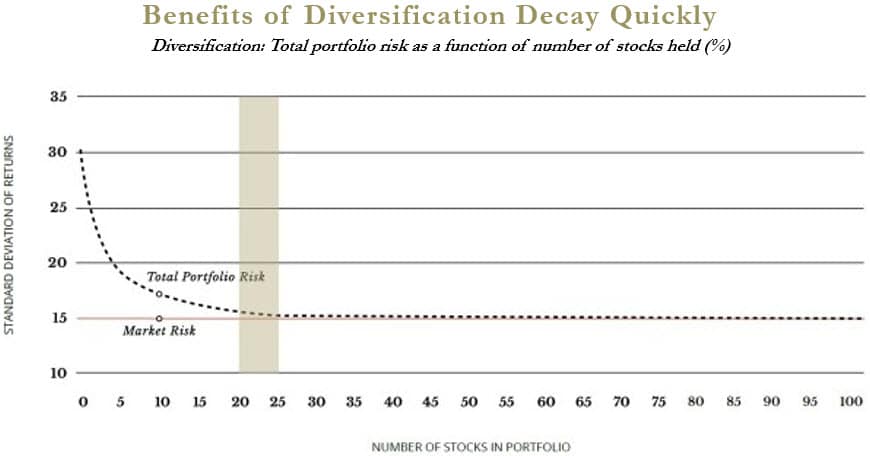

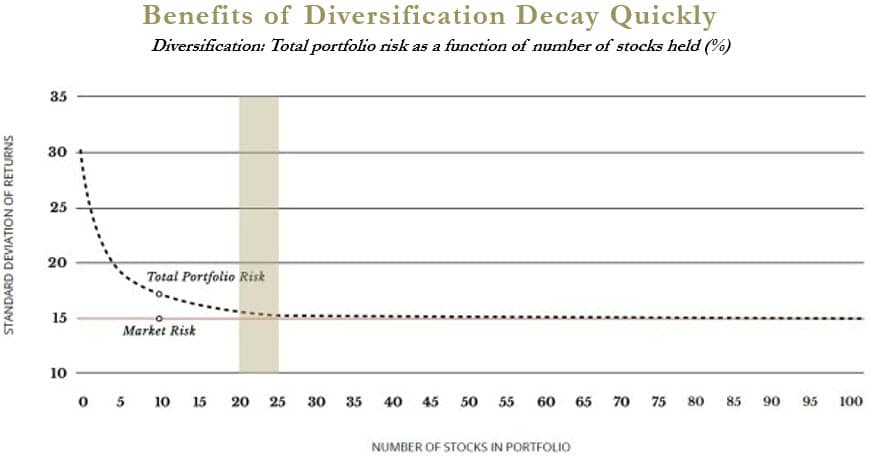

For example, as I have mentioned previously, simply owning a greater number of stocks does not lead to greater diversification. In fact, as my friends over at Ensemble Capital have written before, the diversification benefits of an additional equity component diminish significantly beyond 20-25 holdings:

Beyond that, the market is full of examples of smaller portfolios (in terms of number of positions) outperforming larger ones, while exhibiting less risk in terms of volatility. Consider that the Dow Jones Industrial Average, composed of just 30 stocks, has fared better than the S&P 500 with less volatility, while in the small cap space, the narrower S&P 600 has outperformed the Russell 2000. In sum, what matters most to a portfolio is not the number of stocks in it, but the characteristics of the stocks: the quality and nature of their earnings; factors such as momentum or value, etc.

Given this, it is hard to imagine that there is any real advantage, – in an era of low-cost funds and ETFs that offer investors access to a variety of strategies and portfolios, – to owning poorly-constructed total universe-type portfolios that may charge a few basis points less than alternatives.