As Sam Lee has written, valuation in isolation can be a poor tool for making portfolio allocation decisions. However, when paired with a less quantifiable – though no less real – measure such as investor sentiment, valuation-based timing can be powerful. Consider the cases of two industries, which began the current millennium in utterly different circumstances: telecommunications, which in March of 2000 was at its apex in terms of share of stock market capitalization and investor appetite, and tobacco, which was widely shunned by the investment community, the result of government lawsuits against the industry.

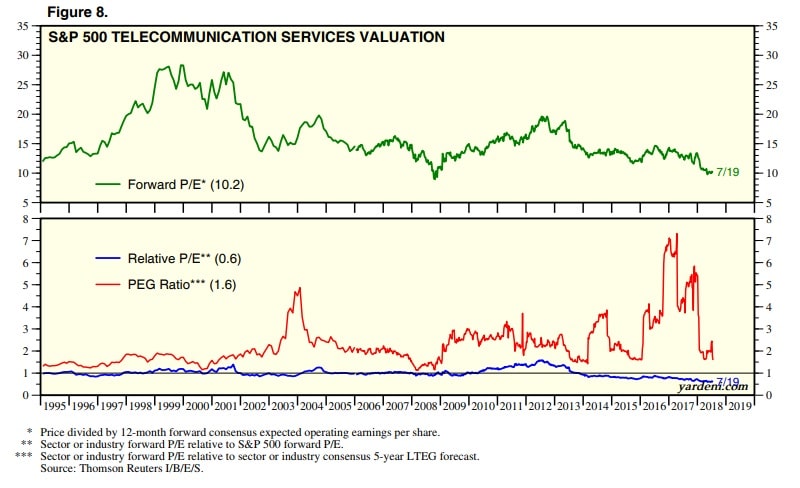

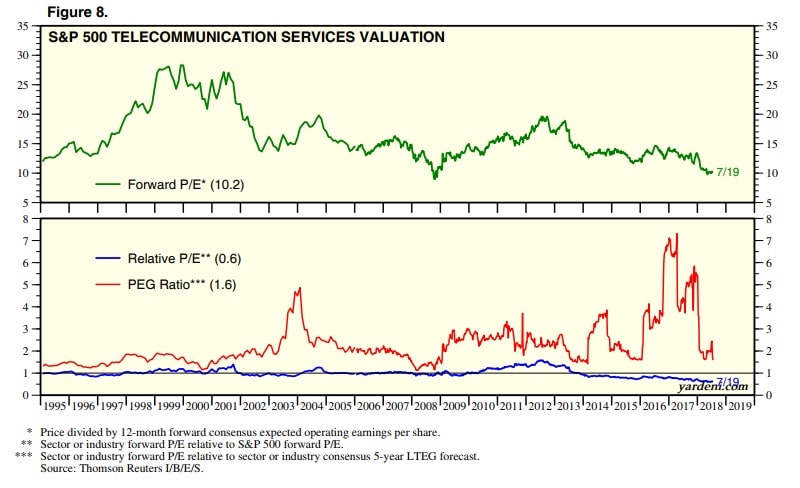

In the case of telecommunications shares, the quick ascendance to market stardom began with deregulation which served as a catalyst to unleash animal spirits in the sector. Valuations climbed steadily as a result, rising above the steady levels of prior years. This steady multiple expansion could have served as reason alone to avoid the sector, but who at the time knew whether deregulation combined with the power of the internet was worth 12-15x earnings as in the past, or 25-30x given the potential of new technologies? (graph via Yardeni):

In any event, telecommunications shares returned greater than 20% annually in the period between deregulation and the peak. However, for observant investors, there were other coincident indicators which signaled that the rise in telecom shares was unsustainable. For instance, between 1995 and the peak, jobs in telecommunications doubled, start-ups sprang up overnight, and infrastructure such as office buildings were going up almost as quickly to accommodate the insatiable demand for industry-related work space. IPOs in the space abounded, and industry players gorged on debt, consuming capital at an amazing rate to lay tens of millions of miles of fiber.

If these signs of a bubble were not ominous enough, influential investors spoke of the future and the amazing potential it held for telecom investors. Emblematic of these futurists was George Gilder, who foresaw a trillion dollar market for telecommunications in which, “there will be no loser.”

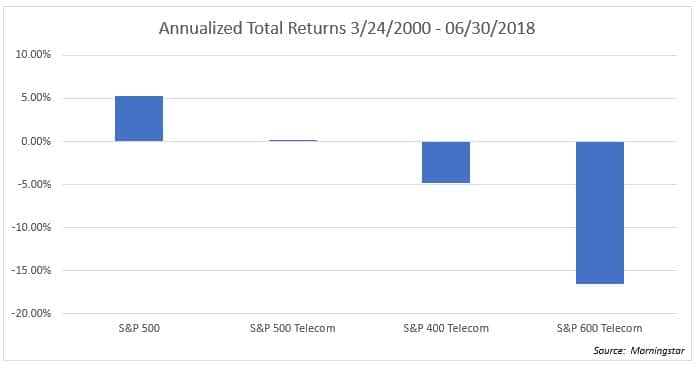

Fast forward to 2018, and we can clearly see that the optimism regarding telecommunications stocks was ill-founded. Large-cap telecommunications shares have been flat since the peak, while mid- and small-cap shares have fared far worse:

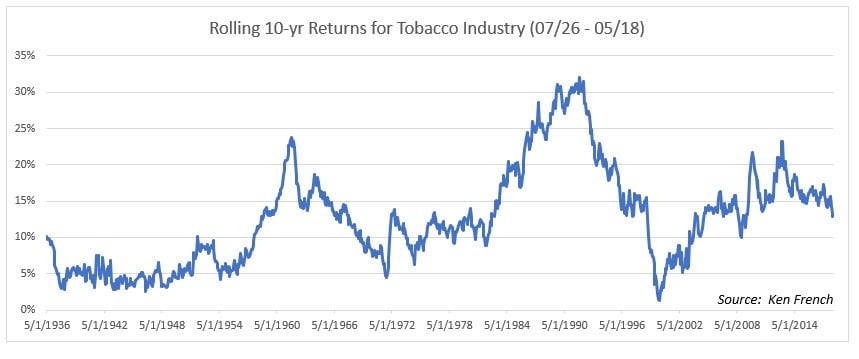

At the time telecom was peaking, the circumstances for tobacco could not have been more different. Lawsuits against the industry by 46 states fostered fears of the industry being bankrupted, and the period marked the nadir for continuous ten-year returns over a seventy-plus year history that included the Great Depression:

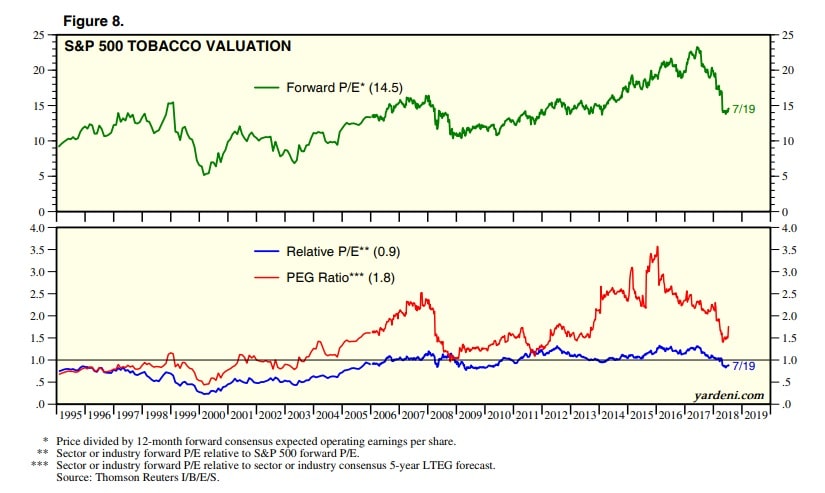

Articles began to appear with titles such as, “Tobacco To Go Bankrupt?” and “Investors Are Swearing Off Tobacco Firms.” The pessimism surrounding the futures of tobacco companies pushed valuations to extremely depressed levels of around 5x the next twelve months’ earnings (via Yardeni):

Yet, buying the fear in tobacco stocks circa 2000 based on valuation and sentiment alone could have proved as foolhardy as embracing the post-deregulation euphoria in telecom. Savvy investors would have noted that while the market was fearful about tobacco’s prospects, the tobacco executives were not. In fact, in what may prove to be some of the most opportunistic share repurchase programs in history, tobacco companies retired shares in droves. RJ Reynolds (now part of British American Tobacco), bought back 19% of its outstanding shares in 1999, and 17% in 2002. Philip Morris, now known as Altria, bought back a similar amount of its market capitalization over the same period. These were, in retrospect, the ultimate buy signals by those most familiar with their companies’ future profitability. Tobacco stocks, of course, not only survived bankruptcy, but went on to outpace the market by a wide margin.

These are examples, obviously, of industries at extremes. Yet they serve as good reminders that rich valuations are best used as warnings signals when paired with corroborating investor enthusiasm and capital raises. Conversely, contrarian opportunity is best seized upon when valuations and pessimism are met with confirming signals by management that the fear is overdone.