Developed by Charles Dow over one hundred years ago, Dow Theory is one of the oldest forms of market analysis, and is still in widespread use by market strategists. Dow Theory is the essence of simplicity; for a market move to be confirmed, both the Dow Jones Industrial Average (or DJIA), and the Dow Jones Transportation Average (DJTA) have to follow one another either to the upside or the downside. The logic behind it is that since the equity markets track the fortunes of the broader economy, both the stocks of companies that manufacture goods and the stocks of companies that ship them should move in lockstep.

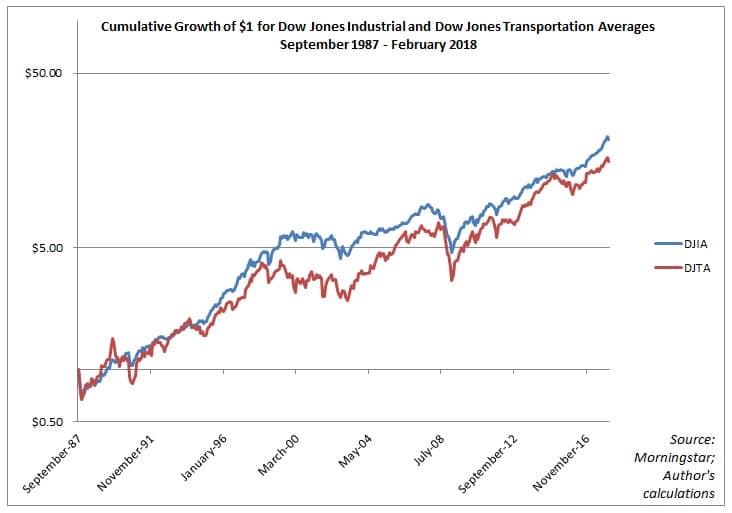

The idea is intuitive, and the returns seem to confirm its merit: going back to September of 1987, the returns for both the DJIA and the DJTA have been fairly similar, with the DJIA returning 10.5% per year through February, and the DJTA returning 9.43%, with the indices tracking each other fairly closely with the exception of the late 1990s tech bubble:

While this method of market analysis has largely stood the test of time, it is important to note that the two indices have evolved dramatically since Charles Dow first stated his theory. For one, in Dow’s time, the DJTA was made up entirely of railroads, which, at that time, made up two-thirds of the entire equity market. The advent of the internal combustion engine and the airplane ushered in new major transportation industries such as trucking and airlines, and these have since been added to the Dow Transports, thus altering to some degree the macro variables that affect the Dow Transports’ performance, and, possibly, also Mr. Dow’s theory.

The reason, I believe, for these changes in relative performance between the two indices is the impact of oil on the components of the Dow Transports. Certainly, if we look at the full 30-year period, there does not seem to be any relationship between oil and the relative performance of the two indices:

But when you break up the period into epochs of “cheap oil” and “expensive oil,” the dynamics change quite a bit. Consider that the price of oil was little changed from ~$20 per barrel from September of 1987 through February of 2003, averaging $21.10 on a monthly basis. However, from March of 2003 through February, the average monthly price of oil more than tripled, averaging $69.10:

During the “cheap oil” period from 1987 through early 2003, the Dow Transports were -64% correlated with energy prices, meaning that as oil prices surged, the Dow Transports declined, and vice versa. This inverse relationship can be seen by comparing by running the same analysis as above, but isolating the period from September 1987 to February 2003:

As can be seen, the Dow Industrials outperformed the Dow Transports as oil prices rose. However, from March 2003 through February 2018, roles reversed, with the transportation index outperforming the industrial index as the price of oil surged, and the U.S. became a major energy producer:

I believe this paradigm shift occurred because of the very different effect a rise in the price of oil has on two major component industries of the Dow Jones Transportation Index, railroads and airlines. To be clear, this is somewhat conjecture on my part as S&P Dow Jones, which manage both the DJIA and the DJTA, does not maintain historical component data for the DJTA. Yet the data seem to indicate that when oil prices were stable, airlines and other components sensitive to energy prices dominated the index, thus making it an inverse reflection of energy prices. Simply look at the relative performance of railroads versus airlines relative to changes in the price of oil:

Currently, railroads constitute roughly 25% of the Dow Transportation Index, roughly double the weighting of the airline components. Given this shift, investors who rely on Dow Theory should at least take into account moves in energy prices before being quick to draw any conclusions from a possible divergence between the Dow Industrials and the Dow Transports, and would do well to monitor the internal components of the latter to ascertain what may really be causing its moves one way or another. This approach would have served investors well in the most recent energy downturn. From September 30th, 2014 to February 2016, the price of oil declined by roughly two-thirds, from more than $90 per barrel to a little more than $30. Over this period, the DJIA was flat, but the Dow Transports were down more than 10%, with railroads leading the decline (-26%). Airlines, on the other hand, rose 26%, thus indicating, in retrospect, that the decline in the transportation average was largely about the decline in oil prices, not about a weakening economy. Investors would do well to learn from this experience.