A friend sent me a Wealth Daily article by Geoffrey Pike who argues that the Fed, by increasing the money supply through zero-interest rate policy and quantitative easing, has distorted the economy and created an artificial boom.

Writes Mr. Pike:

“When a central bank or government significantly increases the money supply that results in bubble activity, then the damage is already done at this point…

“So the big question is whether the U.S. economy – – and U.S. stocks in particular — are in an artificial boom. Is the boom in stocks over the last six years fueled by real growth and prosperity, or is it a result of a loose monetary policy?”

Mr. Pike argues from the supposed position of the “Austrian School” of economics, which places, in my opinion, an overemphasis on central bank activity. It is true, as Mr. Pike says, that the Fed’s balance sheet has ballooned to some $4 trillion in assets since 2008. However, it is not clear, as Mr. Pike claims, that:

“The easy money has flowed into stocks. There has been more asset price inflation than consumer price inflation.”

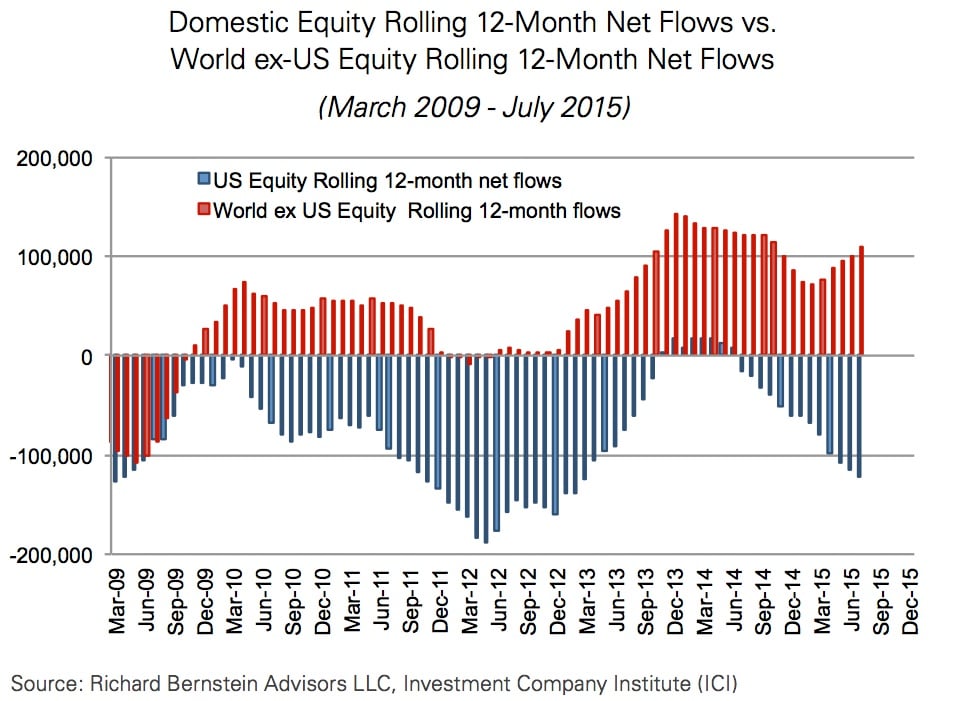

First of all, there is no evidence that “easy money” (whatever that is) has found its way into stocks. In fact, as Business Insider wrote in July, “even though the S&P has more than tripled since the trough of 2009, barely any new money has come into the market.” In fact, throughout most of this bull market, money has flowed out of, not into, U.S. stocks:

Let us direct our attention to Mr. Pike’s second charge, that of asset price inflation. It is important to note that bull markets are defined not necessarily by price action so much as they are by multiple expansion. In other words, in a bull cycle, investors are willing to pay more (i.e. a higher P/E) today for earnings growth tomorrow. In bear markets, the opposite is true. With that in mind, it is interesting to observe that even as the S&P 500 is up almost 200% from its lows of March 2009, the P/E ratio is about where it was in 2010, the first full year of the recovery. Multiples are currently a bit above long-term averages, but they are by no means extraordinary.

One point that could perhaps be conceded to Mr. Pike and the Fed ‘distortinists,’ if you will, could be that by keeping interest rates very low, the Fed has induced a credit bubble by making borrowing for corporations cheap, and that this has stimulated massive buybacks. However, research by Ed Yardeni shows that while credit issuance has indeed risen the last few years, it is basically back to levels previously seen around 2001.

Buybacks have indeed been a huge factor in this bull market, but a better explanation for this phenomenon can be found in Meb Faber’s brilliant book, Shareholder Yield. In Shareholder Yield, Mr. Faber writes that by instituting rule 10b-18 in 1982, the SEC “provided safe harbor for firms conducting share repurchases from stock manipulation charges.” Buybacks have been in favor ever since as a more tax-efficient method of returning cash to shareholders (versus dividends, for example, which are taxed). However, buybacks have taken off since 2004, notes Yardeni, “when corporate bond yields consistently fell below the forward earnings yield of the composite [stock index].” It is important to note that the Fed didn’t implement its zero interest rate policy until 2008, long after this trend had already begun.

I would agree with Mr. Pike that the Fed has intervened too much in this cycle. Just how much the Fed is in the psyche of investors is illustrated by the constant coverage of Fed meetings by CNBC, or the media explaining away daily market fluctuation by claiming investor enthusiasm or disappointment with whatever Fed news there might be that particular day. Take, for example, the explanation for Tuesday’s volatility by respected commentator Cullen Roche, who tweeted that the market faded that day because the “[m]arket was hoping for a word from Fed today & didn’t get it. Too much uncertainty over rate hike…” Never mind that the same uncertainty prevailed Wednesday when stocks jumped.

However, I would argue that the economy, – and perhaps even the market, – would be doing even better than it has been had the Fed not been so interventionist in its policies. As John Tamny writes in his recent book Popular Economics, “[c]redit is scarce because [ex-Fed Chairman] Bernanke told savers that they would get nothing in return for their savings.”

As an optimist, I do not foresee the catastrophe that Mr. Pike and his economic coreligionists predict. The dollar, after years of weakness because of policy preference by both the Bush and Obama administrations, is strengthening, and this is attracting capital once more to our shores. Government deficits are shrinking because Washington is divided and long military commitments are winding down. Unemployment is shrinking as confidence is improving, and also in no small part due to the ending of once interminable unemployment benefits. All of these things are positives for the economy and the markets, and whenever the Fed decides to normalize interest rates, the world will not end.