McKinsey recently published an article about the importance of the industry in which a company does business, stating:

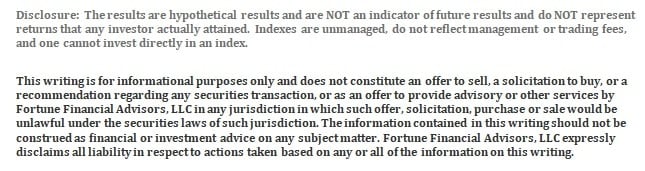

“[A] company’s choice of industry matters a great deal—more than many realize. When we tracked the economic profit of the world’s 2,393 largest companies over the 10 years, we found that about 50% of a firm’s performance compared to the broader corporate universe is driven by what’s happening in its industry, highlighting that ‘where to play’ is perhaps the most critical choice in strategy.”

The author goes on to state that industries such as tobacco, pharmaceuticals, and software are perennially among the top performers in terms of profits, while industries such as utilities and commodities find themselves among the worst performers (graphic via McKinsey):

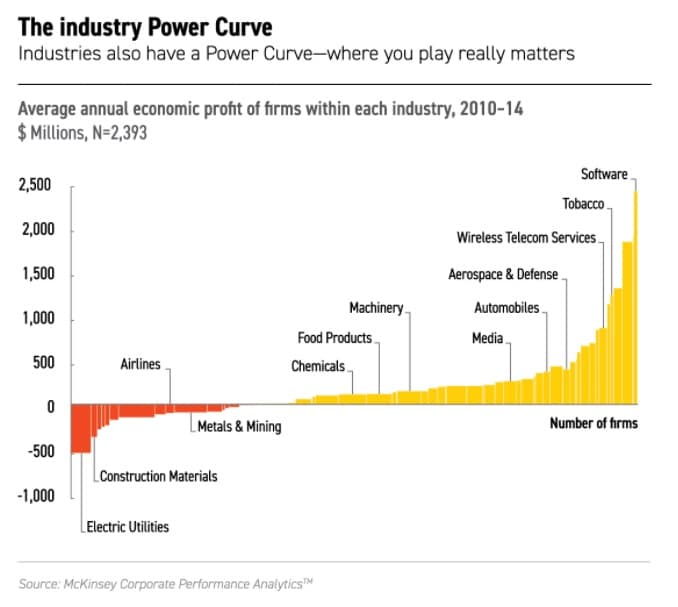

The implications of this study are really quite huge for many discussions going on today in finance. One way to see the impact of this dichotomy between the “good” industries and the “bad” industries is to compare the performance of the stocks in each with the broader market. For example, tobacco stocks have done very well regardless of region of operation…

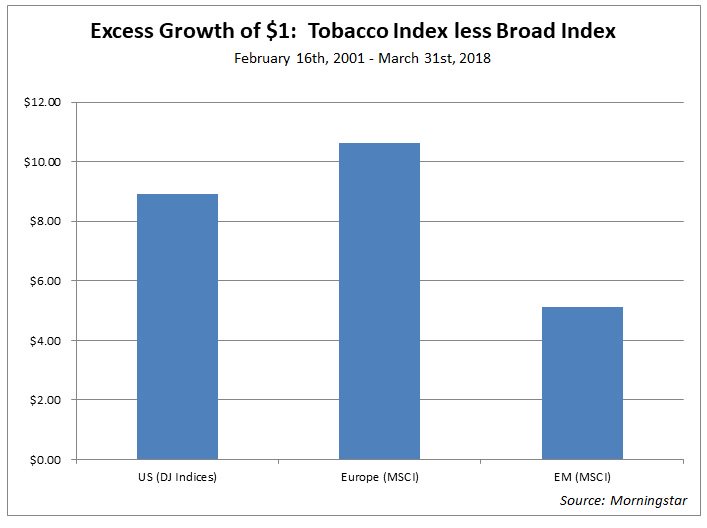

…while airline stocks have generally fared poorly, no matter where they operate:

Secondly, this industry phenomenon has implications for those who allocate their capital based on the perception of a company’s “moat.” That is to say that many investors who base their portfolio decisions on whether a given company has a competitive advantage over its industry peers may instead find it more practical to broaden their scope from the company to the industry level, focusing on those industries with wide and lasting natural moats.

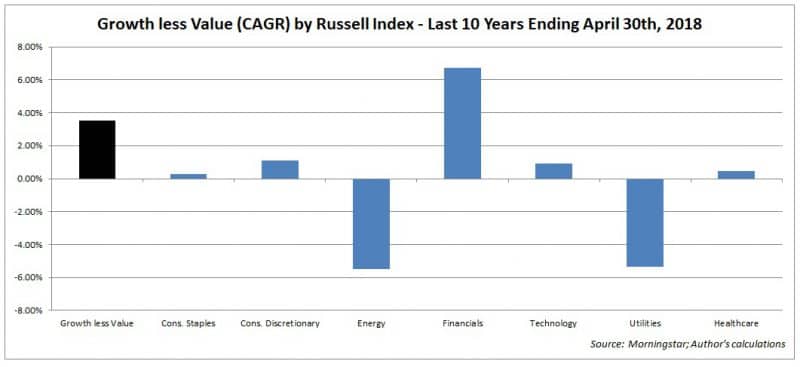

Finally, there are implications for the popular narrative that focuses on the “death of value” investing, which typically cites the Russell 1000 Value’s decade-long lag versus its growth opposite to proclaim a change in paradigm. However, as we discussed last year, much of the subpar performance in this popular value index can be attributable to vast differences in composition by sector between it and the Russell Growth Index. When we dispense with the aggregated indices and compare “growth” and “value” stocks within the same sectors, we can see that the biggest differences in returns were in those sectors the McKinsey study tells us are in the worst performers in terms of economic profit, while the outperformance of growth was marginal at best in the sectors typically associated with industries at the opposite end of the profit spectrum:

Given this, value managers may find it preferable to choose the cheapest stocks in favorable industries, rather than opting for the cheapest stocks in absolute terms, regardless of industry.

In sum, McKinsey puts it rather well: “The role of industry in a company’s position is so substantial that you’d rather be an average company in a great industry than a great company in an average industry.” Investors who focus too much on the fundamentals of a company while ignoring the prospects for its industry do so at their peril.